Strangled himself (being distracted): Messy Data and Suicides in the Bills of Mortality

Content Warning: This post contains subject matter that some may find sensitive or disturbing, be advised. If uncomfortable with this topic, you may support Death By Numbers in other posts.

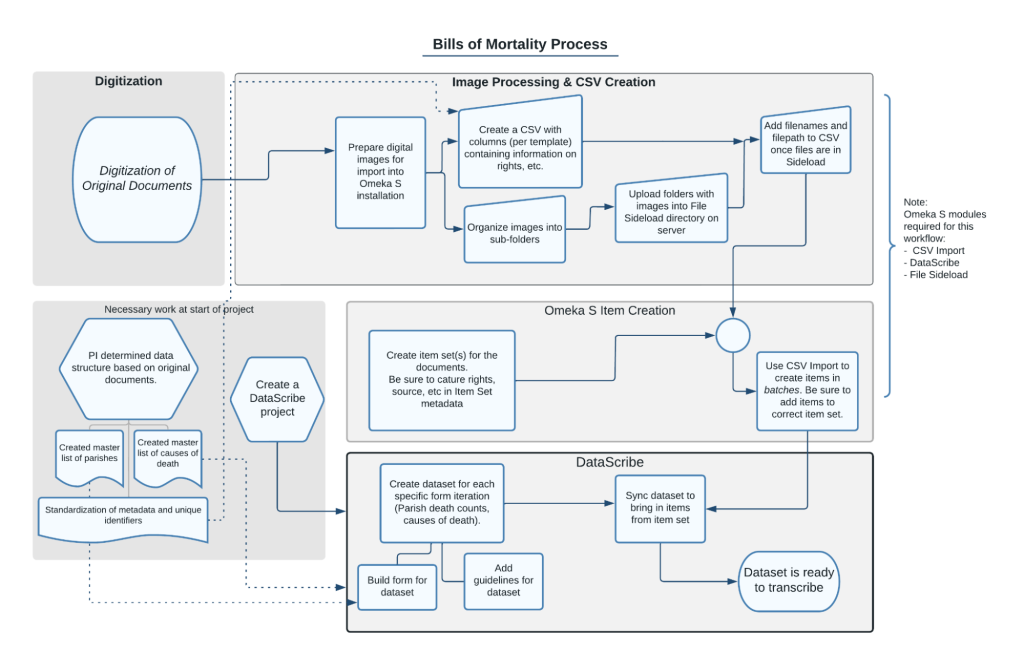

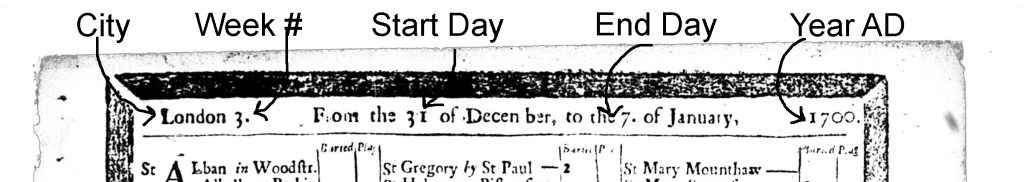

This blog post will be a bit different than a few of our previous posts. Now that we have discussed our project workflow, we are going to begin to discuss the content of the Bills themselves. One thing that we immediately noticed on beginning this project is that suicides are reported on the Bills in a variety of ways that lead to more questions than answers regarding the weekly suicide rate in London. The variety of reports had a lot to do with the religious and legal views on suicide in this era.